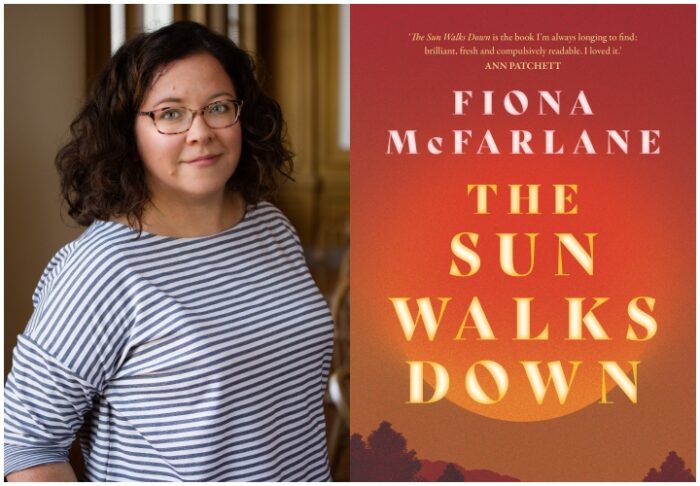

Fiona McFarlane interview: ‘I also rode camels, climbed hills, and learned from the Indigenous owners of the Flinders, the Adnyamathanha”

9th May, 2023

Shortlisted author Fiona McFarlane tells us how she was motivated to write a novel which explores the messy complications of Australian colonial history.

It’s an honour to have been shortlisted for the Walter Scott Prize for Historical Fiction. All writing is solitary, to some extent, but there’s something particularly solitary, I’ve found, about writing an historical novel: that process takes you, in both wonderful and lonely ways, out of your own time and into another. So it’s been especially thrilling to see my book circulating in the present-tense world, sharing the excellent company of the other shortlisted novels.

This failed settlement of the Flinders got me thinking about the region’s history, and Australia’s colonial history more generally, as a series of unsettlements.

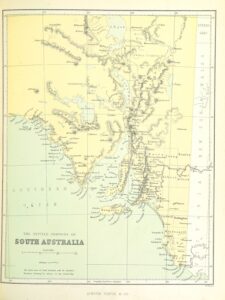

The people and times of The Sun Walks Down lodged in my imagination when I first visited the Flinders Ranges, the arid region of South Australia in which the novel is set. It’s an extraordinary landscape – red dirt, broad plains, deep river gorges, and mountains so ancient they’ve collapsed in on themselves – and it’s full of colonial ruins, from lonely

churches to entire ghost towns. I became fascinated by the lives of the people who once lived here: late-19th-century European settlers who tried, and failed, to grow wheat in the desert. This failed settlement of the Flinders got me thinking about the region’s history, and Australia’s colonial history more generally, as a series of unsettlements. Right away, I knew that I wanted to use this time and place as a way into a novel that interrogated Australian colonial history, and its founding cultural myths.

Research was central to this novel: I researched everything from the fashion for black clothing in the late-19th century to volcanic eruptions to trends in Nordic art. My research involved hours spent in libraries, but I also rode camels, climbed hills, and learned from the Indigenous owners of the Flinders, the Adnyamathanha.

The research for and writing of The Sun Walks Down happened concurrently; I tried to transform my thrilling encounters with the research into sentences as soon as possible, even if I didn’t end up using the sentences in the book. That way, fiction and fact are always interwoven. It’s important to me that the novel feels vivid and lifelike (I want my readers to be immersed in its world) but that it also draws attention to itself as fiction (I want my readers to remember that this is just one version of the past).

The Sun Walks Down invites readers to explore the messy complications of Australian colonial history – which is noisier and stranger than people might think – in order to reflect on the messy complications of being a human in 2023.

Can writing about the past help us to deal with the present and think about the future? Yes, that’s inescapable – all historical fiction is a way of reflecting on the present, and everything that’s made our current world what it is. The Sun Walks Down invites readers to explore the messy complications of Australian colonial history – which is noisier and stranger than people might think – in order to reflect on the messy complications of being a human in 2023. What legacies have we inherited, and how might we reckon with them now and in the future?