Past Winners: 2010 to 2015

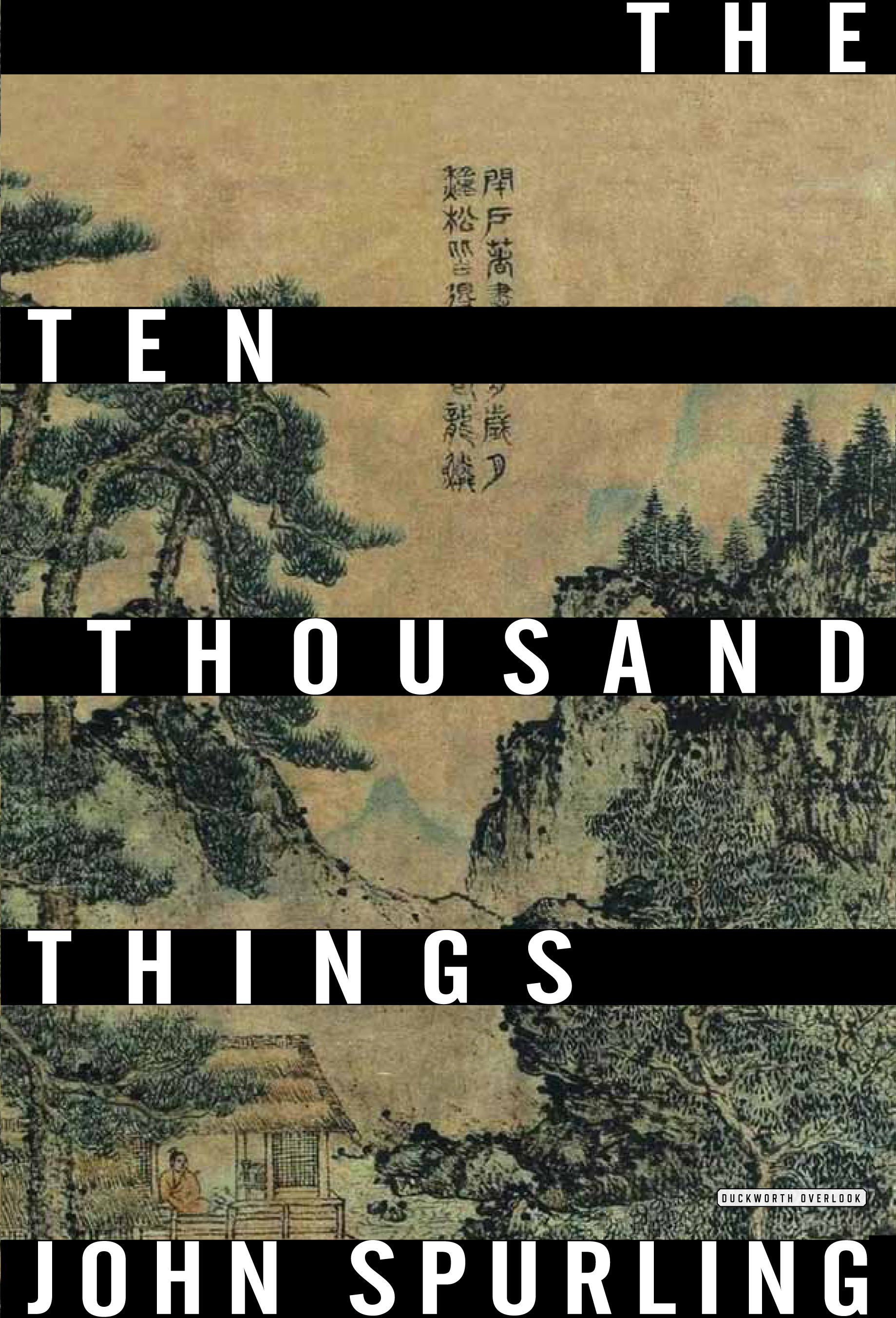

2015: The Ten Thousand Things by John Spurling

The Ten Thousand Things takes place in 14th-century China, during the final years of the Mongol-ruled Yuan Dynasty, and is the story of Wang Meng, one of the era’s four great masters of painting.

The Judges said of the novel:

The Ten Thousand Things is subtle and rewarding. Through John Spurling’s writing you feel as though you are reading Wang Meng’s paintings as he created them. It is a mesmerising, elegantly drawn picture of old imperial China, which feels remarkably modern.

We journeyed and lived ten thousand lives ourselves during the reading and discussion of these books. In the end, it was the illumination shone by John Spurling on this fascinating and little-known period that lit us up for the longest time. It is a book which deserves enormous credit, and we hope that the Walter Scott Prize can help bring it for him.

John Spurling, whose novel was rejected 44 times before being published, was at the Borders Book Festival in Melrose on 13th June 2015 to accept the Prize.

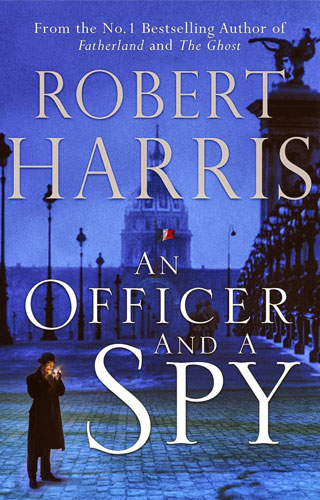

2014: An Officer and a Spy by Robert Harris

This novel is a compelling recreation of a scandal that became one of the most infamous miscarriages of justice, in which a young Jewish officer was convicted of treason in Paris in 1895. It is Robert Harris’ ninth novel; his seventh, Lustrum, was shortlisted for the Walter Scott Prize in 2010. The Judges said of the book:

An Officer and A Spy is a masterwork, a novel written by a story-teller at the pinnacle of his powers. In making compelling literary drama out of the Dreyfus affair, an episode familiar to many, Robert Harris has done something Walter Scott would have been proud of. Exactly 200 years ago, Scott pulled off the same transformation with Waverley and another familiar episode, the 1745 Jacobite Rebellion.

The book is set at the end of the 19th century but its themes have resonated ever since. Cover-ups, anti-semitism and a suspicion of the other, codes and leaks, and the mission of a single individual to force a government to right an injustice – all of these have modern parallels.

In his acceptance speech, Robert Harris cited Sir Walter Scott as a hero of his ever since discovering his Journals as a young man in a second hand bookshop. He quoted from the Journals:

I think I make no habit of feeding on praise, and despise those whom I see greedy for it, as much as I should an underbred fellow who, after eating a cherry-tart, proceeded to lick the plate.

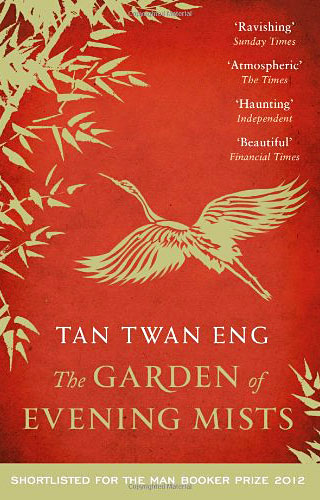

2013: The Garden of Evening Mists by Tan Twan Eng

This novel deals with the legacy of the Second World War and the Malayan Emergency of the 1950s, through the story of a woman who has been interned in a Japanese POW camp and seeks to build a garden in memory of her sister in the Cameron Highlands. The Judges said of the book:

The poignancy of both remembering and forgetting is what this book is all about. One of the strengths of the Walter Scott Prize is that we can be broad in our reach. Set in the jungle-clad highlands of Malaya, this year’s winner leads us into the troubled aftermath of World War Two. It is pungent and atmospheric; a rich, enigmatic, layered novel in which landscapes part and merge, and part again.

Tan Twan Eng said of the Prize:

To be the first writer from the Commonwealth to win the Walter Scott Prize was a tremendous honour. Because of the Prize, The Garden of Evening Mists has now been read by countless people who would never have picked it up before. The Walter Scott Prize will only go from strength to strength and take its place as one of the premier literary prizes in the world.

2012: On Canaan’s Side by Sebastian Barry

Narrated by Lilly Bere, On Canaan’s Side opens as she mourns the loss of her grandson, Bill. The story then goes back to the moment she was forced to flee Sligo, at the end of the First World War, and follows her life through into the new world of America, a world filled with hope and danger. The Judges said:

There was little more than a whisker between On Canaan’s Side and the other five shortlisted novels, but it was its drive, and its sustained power than persuaded us to award the Walter Scott Prize to Sebastian Barry. A work of immense power, the book is muscular and complete, and the author wears his learning lightly. Every character is fully drawn and utterly memorable.

Sebastian Barry said of winning the Prize:

I’m uncharacteristically speechless. I really was not expecting to win – just look at the other authors on the shortlist. My first encounter with Walter Scott was unlocking a trunk in my grandfather’s attic which contained the Waverley novels. I felt as if I was excavating a tomb. I think that is an appropriate way to encounter a writer – as if you were literally retrieving him from the damp and history of your grandfather’s life.

2011: The Long Song by Andrea Levy

This novel tells the story of the last turbulent years of slavery and the early years of freedom in nineteenth-century Jamaica. The Judges said of the book:

Andrea Levy brings to this story such personal understanding and imaginative depth that her characters leap from the page, with all the resilience, humour and complexity of real people. There are no clichés or stereotypes here. The Long Song is quite simply a celebration of the triumphant human spirit in times of great adversity.

Andrea Levy said of winning the Prize:

I’m very honoured to receive the Walter Scott Prize. This is a generous literary prize which focuses attention on an important aspect of the role of fiction. Fiction can – and must –

step in where historians cannot go because of the rigour of their discipline. Fiction can breathe life into our lost or forgotten histories. My subject matter has always been key to what and why I write – the shared history of Britain and those Caribbean islands of my heritage. I would like to remember all those once enslaved people of the Caribbean who helped to make us all what we are today.

2010: Wolf Hall by Hilary Mantel

Wolf Hall was the first in Hilary Mantel’s masterly series of fictionalised biography documenting the rapid rise to power of Thomas Cromwell in the court of Henry VIII, through to the death of Sir Thomas More. The Judges said of the book:

For once, you can believe the hype. This is as good as the historical novel gets – immersive, constantly engaging, beautifully crafted, and compulsively readable. Choose any superlative: it will fail this book. Mantel’s empathy for, and assimilation of, her world is so seamless and effortless as to be almost disturbing. Each book on the shortlist is deserving of the prize, but Wolf Hall was for us the outright winner, in a class of its own.

Hilary Mantel said on winning the Prize:

I am astonished and delighted and gratified to be the first winner of the Walter Scott prize. Intense involvement in history was what started me writing. And now – although I hope to go on writing contemporary novels – the challenges and perplexities of historical fiction have become my preoccupation. And just in time, because this has been an interesting year for writers and readers of the historical novel – perhaps a turning point year.

But much the best thing that has happened for lovers of historical fiction is the founding of this prize. When I first heard of it I couldn’t quite believe it; it is such a startlingly generous and imaginative gesture, an appropriately old-fashioned act of patronage of the arts. In the years to come, this prize will magnetise attention and stimulate debate.